July 2013

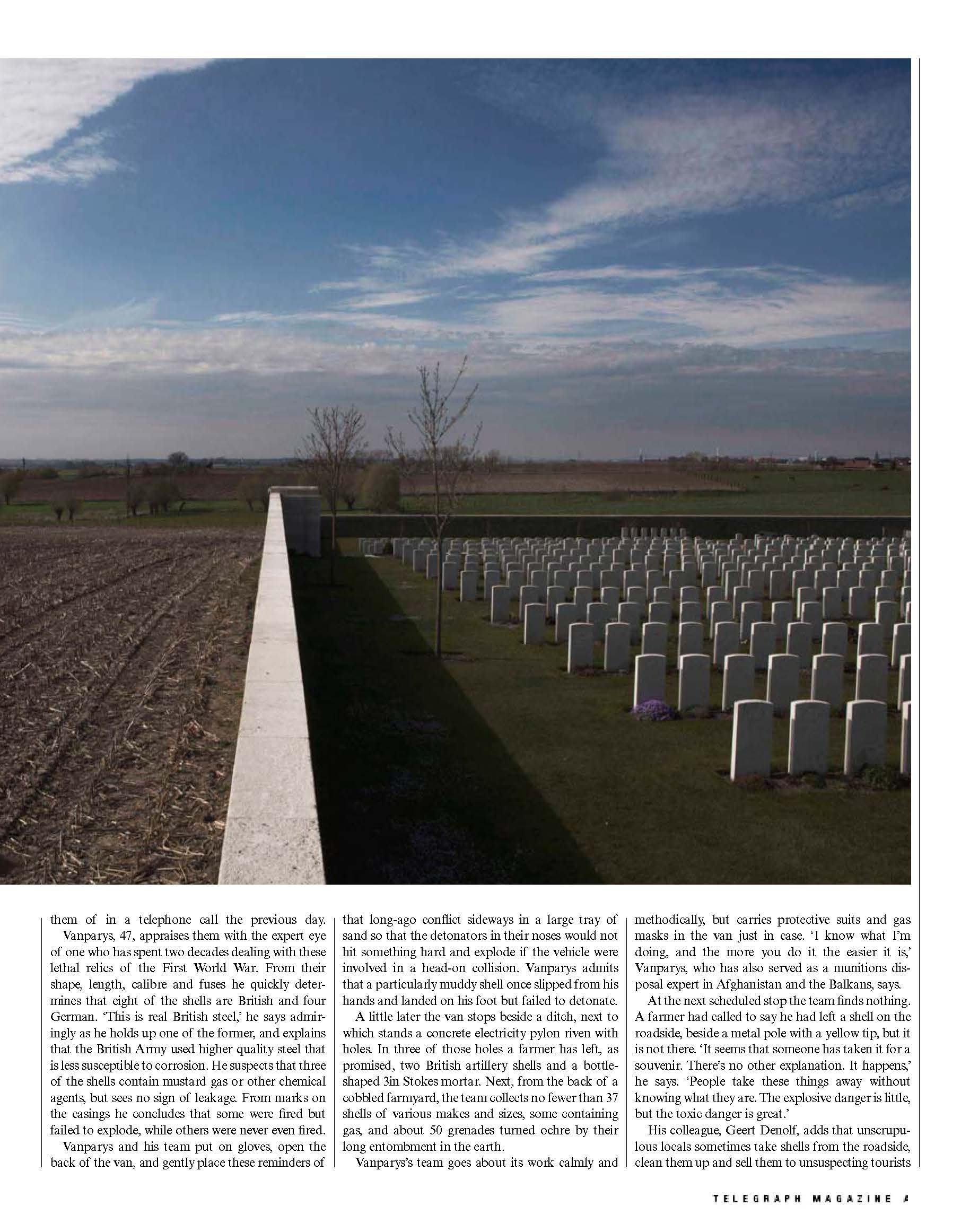

It is 9am, and the sun has yet to burn the mist off the rich flat farmland of western Flanders when Dirk Vanparys and two other Belgian soldiers leave their base for their daily tour of the old Western Front. They drive in a large white Mercedes van down straight lanes flanked by vast open fields of wheat and potatoes broken only by the occasional copse or line of poplars. There is no hint of the horrors that engulfed this tranquil landscape nearly a century ago; nothing to remind the casual visitor of the ghastly war of attrition fought in the nearby trenches of Passchendaele and the Ypres Salient. Nothing, that is, until Vanparys stops where a dirt track joins the road beside a brick farmhouse. There, piled on the grass, are 12ft-long shells encrusted with mud and rust – two more than the farmer had told them of in a telephone call the previous day.

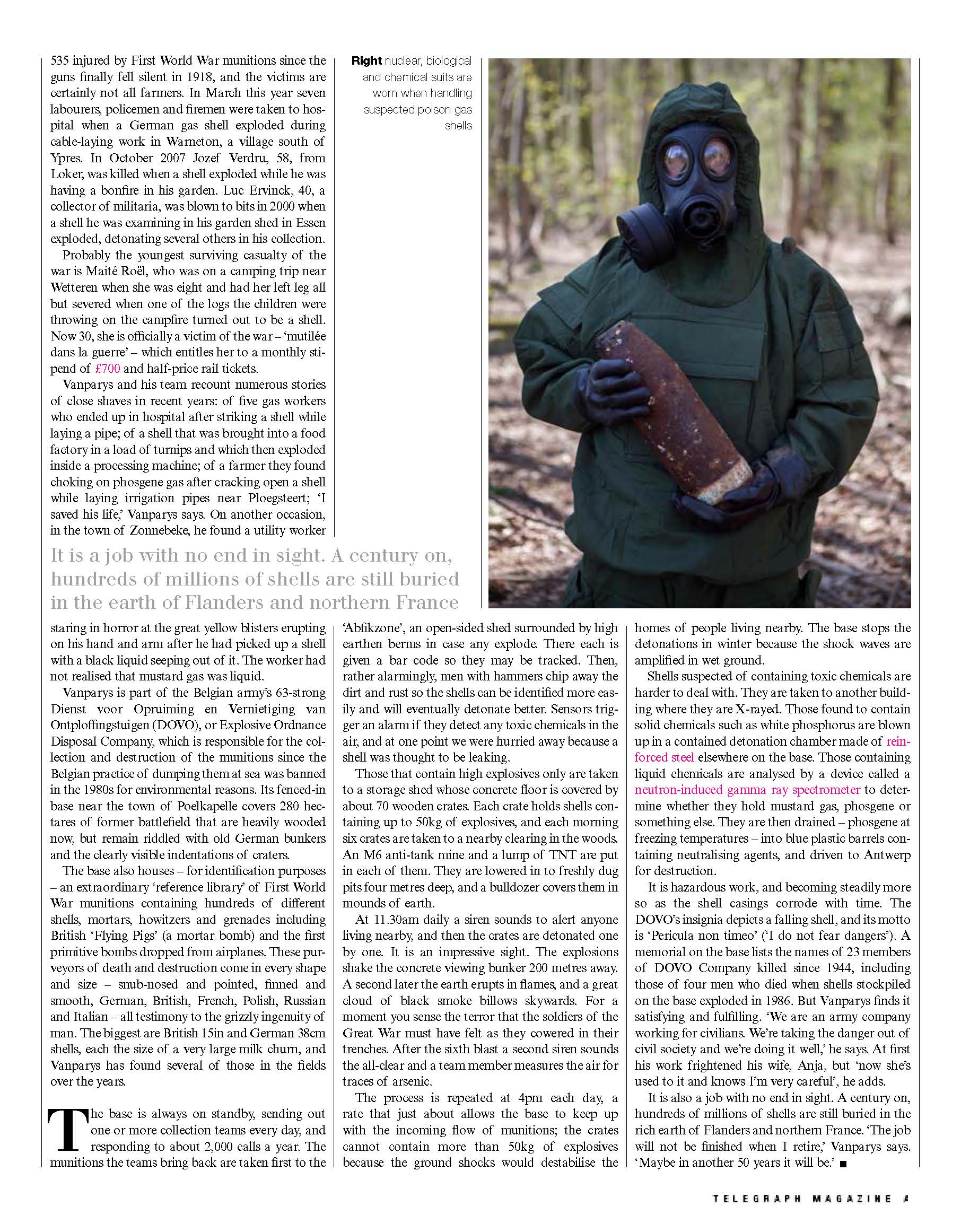

Vanparys, 47, appraises them with the expert eye of one who has spent two decades dealing with these lethal relics of the First World War. From their shape, length, calibre and fuses he quickly determines that eight of the shells are British and four German. ‘This is real British steel,’ he says admiringly as he holds up one of the former, and explains that the British Army used higher quality steel that is less susceptible to corrosion. He suspects that three of the shells contain mustard gas or other chemical agents, but sees no sign of leakage. From marks on the casings he concludes that some were fired but failed to explode, while others were never even fired.

Vanparys and his team put on gloves, open the back of the van, and gently place these reminders of that long-ago conflict sideways in a large tray of sand so that the detonators in their noses would not hit something hard and explode if the vehicle were involved in a head-on collision. Vanparys tells me that a particularly muddy shell once slipped from his hands and landed on his foot but failed to detonate.

A little later the van stops beside a ditch, next to which stands a concrete electricity pylon riven with holes. In three of those holes a farmer has left, as promised, two British artillery shells and a bottle-shaped 3in Stokes mortar. Next, from the back of a cobbled farmyard, the team collects no fewer than 37 shells of various makes and sizes, some containing gas, and about 50 grenades turned ochre by their long entombment in the earth.

Vanparys’s team goes about its work calmly and methodically, but carries protective suits and gas masks in the van just in case. ‘I know what I’m doing, and the more you do it the easier it is,’ Vanparys, who has also served as a munitions disposal expert in Afghanistan and the Balkans, says.

At the next scheduled stop the team finds nothing. A farmer had called to say he had left a shell on the roadside, beside a metal pole with a yellow tip, but it is not there. ‘It seems that someone has taken it for a souvenir. There’s no other explanation. It happens,’ he says. ‘People take these things away without knowing what they are. The explosive danger is little, but the toxic danger is great.’

His colleague Geert Denolf adds that unscrupulous locals sometimes take shells from the roadside, clean them up and sell them to unsuspecting tourists in the markets of Ypres. ‘It will be a booming business during the centenary years,’ he predicts. ‘Booming’ in more senses than one, perhaps.

And so the day goes on. By the time the team completes the last of its 13 stops it has collected 73 shells and 57 assorted grenades and fuses. Most had been found by farmers in their fields, a handful by construction or utility workers digging holes, a couple by people working in their gardens. Vanparys had retrieved one German shell from a potato field, only to spot another protruding from a ridge of earth a yard away. ‘It’s a fairly typical day,’ he says as his team returns to its base with its haul.

Nearly 100 years on the Belgian and French authorities are still clearing up the debris of the Great War. In fact their so-called ‘Iron Harvests’ are bigger now than they were several decades ago, largely because the farmers have heavier and more sophisticated tractors that plough much deeper, and because more construction work is taking place in the towns and villages along the old Western Front. Last year alone the Belgian military collected 105 tons of munitions, many containing toxic chemicals, and the French police, who run a similar collection service out of a base near Arras, 80 tons. The year before the combined total was 274 tons. Sometimes, when a long-lost arms cache or depot is discovered, the total is higher still. In 2004, for example, 3,000 German artillery shells were found at a single site in Dadizele, east of Ypres.

Such large volumes are not quite as surprising as they sound. Between 1914 and 1918 the opposing armies fired an estimated 1.45 billion shells at each other, of which about 66 million contained mustard gas or other toxic chemicals such as phosgene or white phosphorus. As Vanparys says, ‘The three richest countries in the world at that time [Britain, Germany and France] went bankrupt in four years through producing so much war material.’ Moreover most of the shelling occurred along a front line that changed very little during those four years. Attacks were often preceded by days of non-stop bombardment of enemy positions, causing the ground to become so churned up and soft that up to a third of the shells simply failed to explode on impact.

A century on the casualty figures also continue to rise. Every year or two a farmer detonates a shell while ploughing his fields and destroys if not himself, then at least his tractor. More would be killed or wounded were it not for the fact that they almost always plough in the same direction, giving the buried shells glancing blows that gradually nudge them into line so their noses are less likely to be hit. The Belgian government has paid out nearly €140,000 in compensation over the past three years for damage caused to tractors, ploughs and combine harvesters by First World War munitions.

‘I don’t worry, but my wife does,’ a farmer called Van Christophe said as he took a break from planting potatoes in a field near the base. He reckons he finds 10 or 15 shells a year on his land. ‘I simply put them to one side and normally there’s no problem.’

In the Ypres area 358 people have been killed and 535 injured by First World War munitions since the guns finally fell silent in 1918, and the victims are certainly not all farmers. In March this year seven labourers, policemen and firemen were taken to hospital when a German gas shell exploded during cable-laying work in Warneton, a village south of Ypres. In October 2007 Jozef Verdru, 58, from Loker, was killed when a shell exploded while he was having a bonfire in his garden. Luc Ervinck, 40, a collector of militaria, was blown up in 2000 when a shell he was examining in his garden shed in Essen exploded, detonating several others in his collection.

Probably the youngest surviving casualty of the war is Maité Roël, who was on a camping trip near Wetteren when she was eight and had her left leg all but severed when one of the logs the children were throwing on the campfire turned out to be a shell. Now 30 she is officially a victim of the war – ‘mutilée dans la guerre’ – which entitles her to a monthly stipend of £700 and half-price rail tickets.

Vanparys and his team recount numerous stories of close shaves in recent years: of five gas workers who ended up in hospital after striking a shell while laying a pipe; of a shell that was brought into a food factory in a load of turnips and which then exploded inside a processing machine; of a farmer they found choking on phosgene gas after cracking open a shell while laying irrigation pipes near Ploegsteert; ‘I saved his life,’ Vanparys says. On another occasion, in the town of Zonnebeke, he found a utility worker staring in horror at the great yellow blisters erupting on his hand and arm after he had picked up a shell with a black liquid seeping out of it. The worker had not realised that mustard gas was liquid.

Vanparys is part of the Belgian army’s 63-strong Dienst voor Opruiming en Vernietiging van Ontploffingstuigen (DOVO), or Explosive Ordnance Disposal Company, which is responsible for the collection and destruction of the munitions since the Belgian practice of dumping them at sea was banned in the 1980s for environmental reasons. Its fenced-in base near the town of Poelkapelle covers 280 hectares of former battlefield that are heavily wooded now, but remain riddled with old German bunkers and the clearly visible indentations of craters.

The base also houses – for identification purposes – an extraordinary ‘reference library’ of munitions containing hundreds of different shells, mortars, howitzers and grenades including British ‘Flying Pigs’ (a mortar bomb) and the first primitive bombs dropped from airplanes. These purveyors of death and destruction come in every shape and size – snub-nosed and pointed, finned and smooth, German, British, French, Polish, Russian and Italian – all testimony to the grizzly ingenuity of man. The biggest are British 15in and German 38cm shells, each the size of a very large milk churn, and Vanparys has found several of those in the fields over the years.

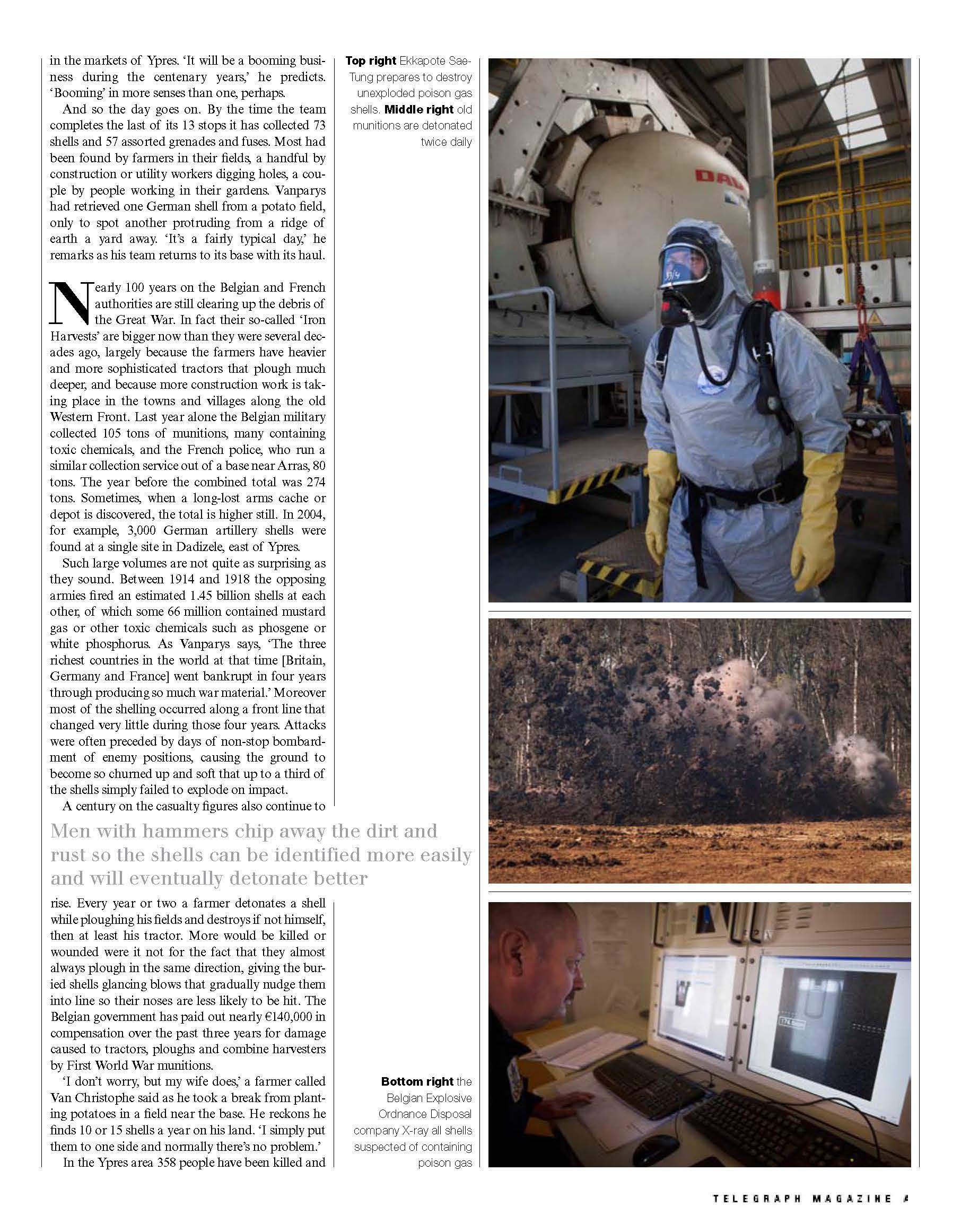

The base is always on standby, sending out one or more collection teams every day, and responding to about 2,000 calls a year. The munitions the teams bring back are taken first to the ‘Abfikzone’, an open-sided shed surrounded by high earthen berms in case any explode. There each is given a bar code so they may be tracked. Then, rather alarmingly, men with hammers chip away the dirt and rust so the shells can be identified more easily and will eventually detonate better. Sensors trigger an alarm if they detect any toxic chemicals in the air, and at one point we were hurried away because a shell was thought to be leaking.

Those that contain high explosives only are taken to a storage shed whose concrete floor is covered by about 70 wooden crates. Each crate holds shells containing up to 50kg of explosives, and each morning six crates are taken to a nearby clearing in the woods. An M6 anti-tank mine and a lump of TNT are put in each of them. They are lowered in to freshly dug pits four metres deep, and a bulldozer covers them in mounds of earth.

At 11.30am daily a siren sounds to alert anyone living nearby, and then the crates are detonated one by one. It is an impressive sight. The explosions shake the concrete viewing bunker 200 metres away. A second later the earth erupts in flames, and a great cloud of black smoke billows skywards. For a moment you sense the terror that the soldiers of the Great War must have felt as they cowered in their trenches. After the sixth blast a second siren sounds the all-clear and a team member measures the air for traces of arsenic.

The process is repeated at 4pm each day, a rate that just about allows the base to keep up with the incoming flow of munitions; the crates cannot contain more than 50kg of explosives because the ground shocks would destabilise the homes of people living nearby. The base stops the detonations in winter because the shock waves are amplified in wet ground.

Shells suspected of containing toxic chemicals are harder to deal with. They are taken to another building where they are X-rayed. Those found to contain solid chemicals such as white phosphorus are blown up in a contained detonation chamber made of reinforced steel elsewhere on the base. Those containing liquid chemicals are analysed by a device called a neutron-induced gamma ray spectrometer to determine whether they hold mustard gas, phosgene or something else. They are then drained – phosgene at freezing temperatures – into blue plastic barrels containing neutralising agents, and driven to Antwerp for destruction.

It is hazardous work, and becoming steadily more so as the shell casings corrode with time. The DOVO’s insignia depicts a falling shell, and its motto is ‘Pericula non timeo’ (‘I do not fear dangers’). A memorial on the base lists the names of 23 members of DOVO Company killed since 1944, including those of four men who died when shells stockpiled on the base exploded in 1986. But Vanparys finds it satisfying and fulfilling. ‘We are an army company working for civilians. We are taking the danger out of civil society and we are doing it well,’ he says. At first his work frightened his wife, Anja, but ‘now she’s used to it and knows I’m very careful,’ he adds.

It is also a job with no end in sight. A century on, hundreds of millions of shells are still buried in the rich earth of Flanders and northern France. ‘The job will not be finished when I retire,’ Vanparys says. ‘Maybe in another 50 years it will be.’