September 2013

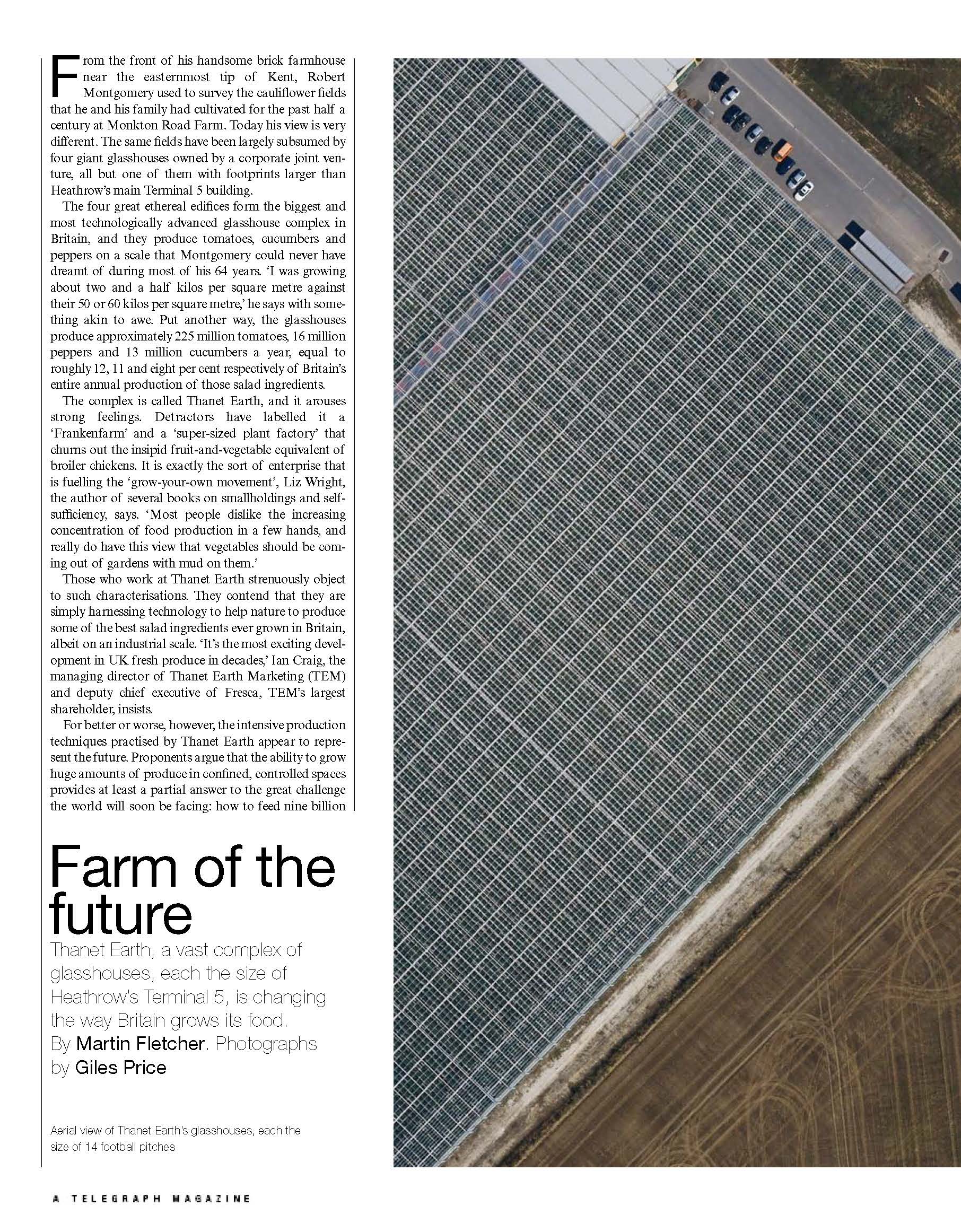

From the front of his handsome brick farmhouse near the easternmost tip of Kent, Robert Montgomery used to survey the cauliflower fields that he and his family had cultivated for the past half a century at Monkton Road Farm. Today his view is very different. On those same fields stand four giant glasshouses owned by a corporate joint venture, all but one of them with footprints larger than Heathrow’s main Terminal 5 building.

The four great ethereal edifices form the biggest and most technologically advanced glasshouse complex in Britain, and they produce tomatoes, cucumbers and peppers on a scale that Montgomery could never have dreamt of during most of his 64 years. 'I was growing about two and a half kilos per square metre against their 50 or 60 kilos per square metre,’ he says with something akin to awe. Put another way, the glasshouses produce approximately 225 million tomatoes, 16 million peppers and 13 million cucumbers a year, equal to roughly 12, 11 and eight per cent respectively of Britain’s entire annual production of those salad ingredients.

The complex is called Thanet Earth, and it arouses strong feelings. Its vocal detractors have labelled it a 'Frankenfarm’ and a 'super-sized plant factory’ that churns out the insipid fruit-and-vegetable equivalent of broiler chickens. It is exactly the sort of enterprise that is fuelling the grow-your-own movement, according to Liz Wright, the author of several books on smallholdings and self-sufficiency, who feels that most people dislike the increasing concentration of food production in a few hands, and really do have the view that vegetables should be coming out of gardens with mud on them.

Those who work at Thanet Earth strenuously object to such characterisations. They contend that they are simply harnessing technology to help nature to produce some of the best salad ingredients ever grown in Britain, albeit on an industrial scale. 'It’s the most exciting development in UK fresh produce in decades,’ Ian Craig, the managing director of Thanet Earth Marketing (TEM) and the deputy chief executive of Fresca, TEM’s largest shareholder, insists.

For better or worse, however, the intensive production techniques practised by Thanet Earth appear to represent the future. Proponents argue that the ability to grow huge amounts of produce in confined, controlled spaces provides at least a partial answer to the great challenge the world will soon be facing: how to feed nine billion people while contending with the potentially devastating consequences of climate change.

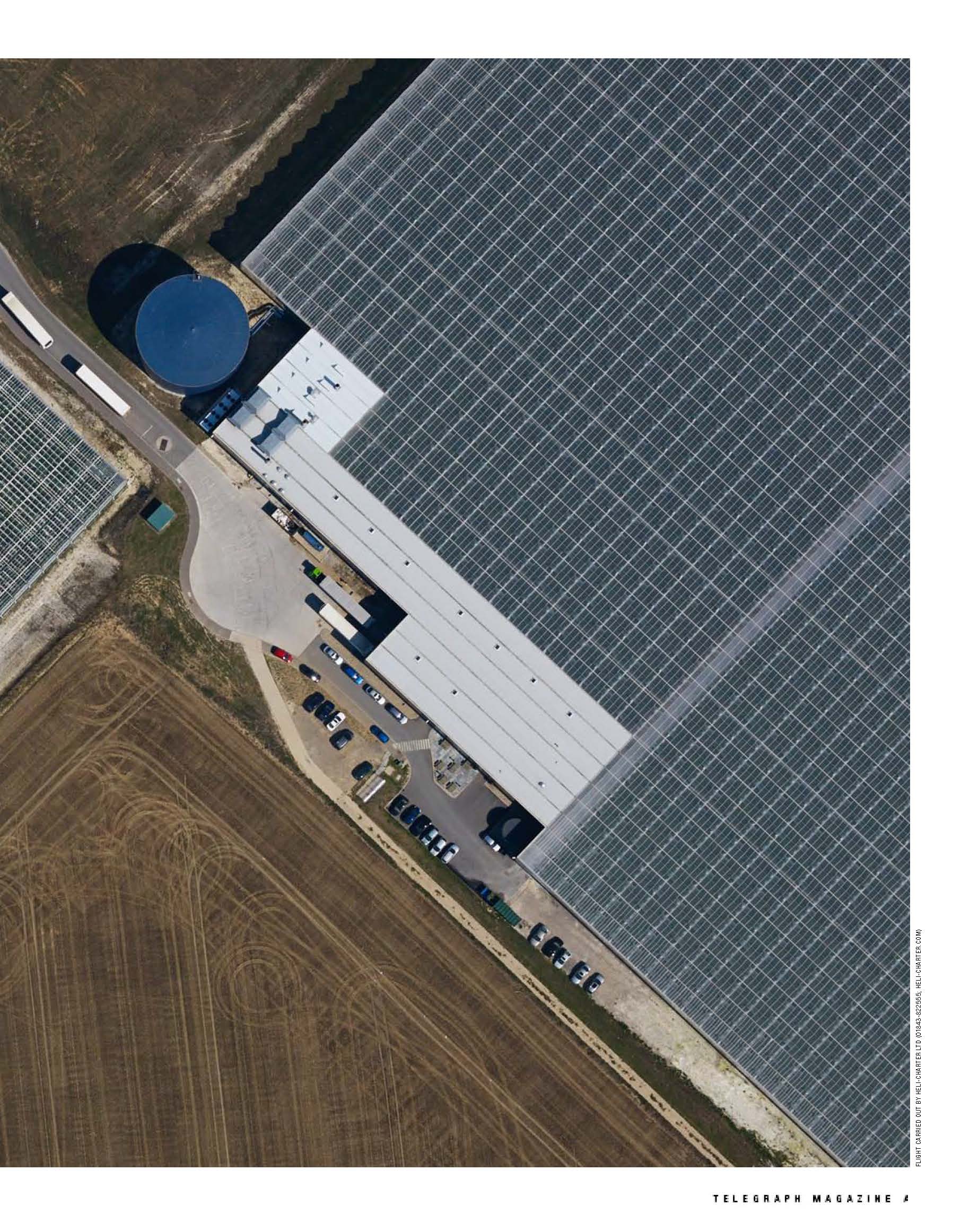

Thanet Earth is such an enormous enterprise that it has its own road signs on the A299, though in truth they are scarcely necessary because the glasshouses stand on open, elevated ground and dominate the surrounding farmland. Throughout the day the security barrier at the entrance to the £135 million complex rises and falls as heavily laden juggernauts carry its produce away to Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Marks & Spencer.

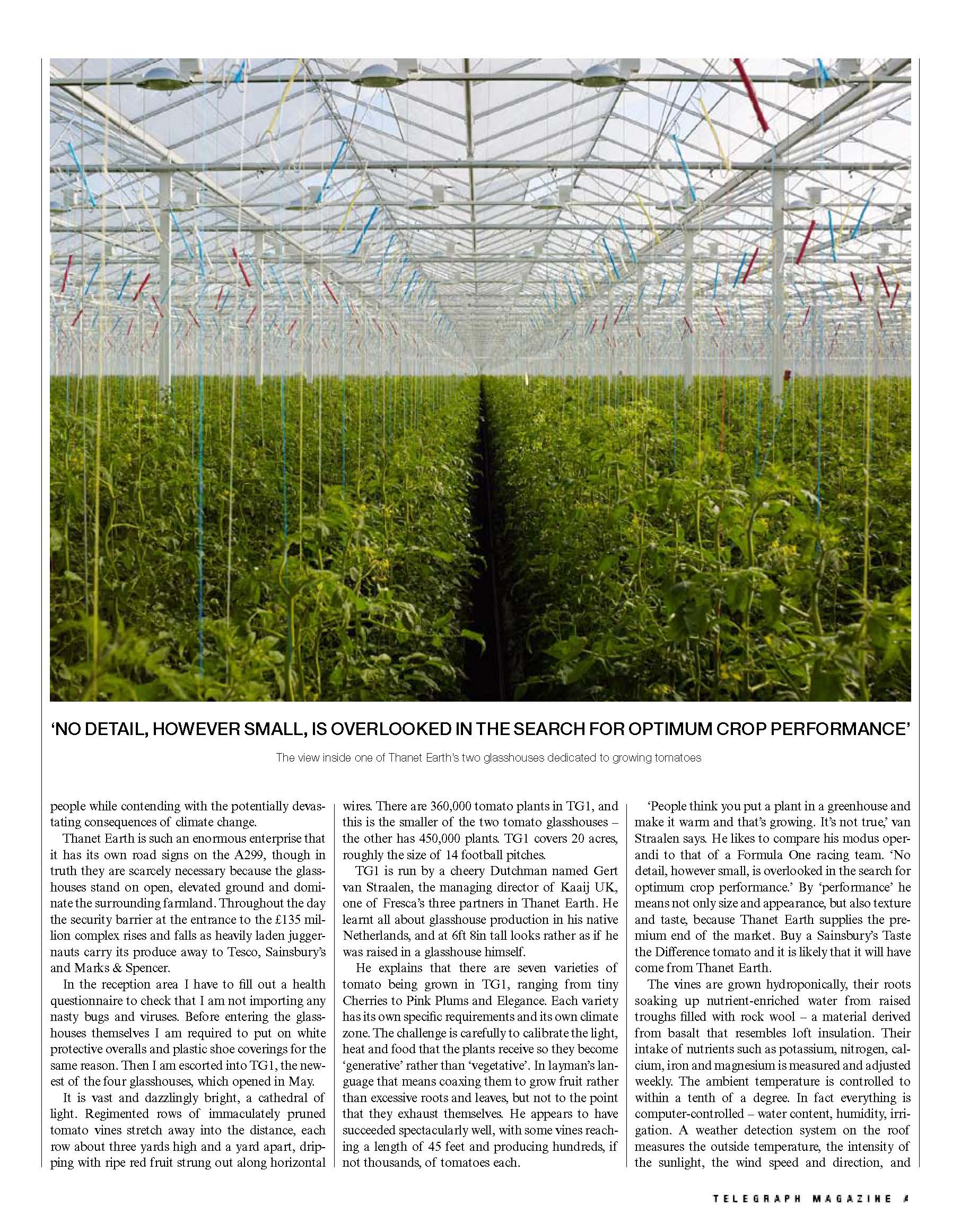

In the reception area I have to fill out a health questionnaire to check that I am not importing any nasty bugs and viruses. Before entering the glasshouses themselves I am required to put on white protective overalls and plastic shoe coverings for the same reason. Then I am escorted into TG1, the newest of the four glasshouses, which opened in May.

It is vast and dazzlingly bright, a cathedral of light. Regimented rows of immaculately pruned tomato vines stretch away into the distance, each row about three yards high and a yard apart, dripping with ripe red fruit strung out along horizontal wires. There are 360,000 tomato plants in TG1, and this is the smaller of the two tomato glasshouses – the other has 450,000 plants. TG1 covers 20 acres, roughly the size of 14 football pitches.

TG1 is run by a cheery Dutchman named Gert van Straalen, the managing director of Kaaij UK, one of Fresca’s three partners in Thanet Earth. He learnt all about glasshouse production in his native Netherlands, and at 6ft 8in tall looks rather as if he was raised in a glasshouse himself.

He explains that there are seven varieties of tomato being grown in TG1, ranging from tiny cherries to Pink Plums and Elegance. Each variety has its own specific requirements and its own climate zone. The challenge is carefully to calibrate the light, heat and food that the plants receive so they become 'generative’ rather than 'vegetative’. In layman’s language that means coaxing them to grow fruit rather than excessive roots and leaves, but not to the point that they exhaust themselves. He appears to have succeeded spectacularly well, with some vines reaching a length of 45 feet and producing hundreds, if not thousands, of tomatoes each.

'People think you put a plant in a greenhouse and make it warm and that’s growing. It’s not true,’ van Straalen says. He likes to compare his modus operandi to that of a Formula One racing team. 'No detail, however small, is overlooked in the search for optimum crop performance.’ By 'performance’ he means not only size and appearance, but also texture and taste, because Thanet Earth supplies the premium end of the market. Buy a Sainsbury’s Taste the Difference tomato and it is likely that it will have come from Thanet Earth.

The vines are grown hydroponically, their roots soaking up nutrient-enriched water from raised troughs filled with rock wool – a material derived from basalt that resembles loft insulation. Their intake of nutrients such as potassium, nitrogen, calcium, iron and magnesium is measured and adjusted weekly. The ambient temperature is controlled to within a tenth of a degree. In fact everything is computer-controlled – water content, humidity, irrigation. A weather detection system on the roof measures the outside temperature, the intensity of the sunlight, the wind speed and direction, and adjusts the system of vents and blinds accordingly.

Light is the single most important factor. 'One per cent more light gives one per cent more production,’ van Straalen explains. That is why the complex is built where it is. The big-skied, sea-girt Isle of Thanet enjoys more light than almost anywhere else in Britain, and therefore more precious joules for the plants to photosynthesise. The operation would not be economically viable north of London because there is too much cloud cover.

The roofs are made of a special glass with low iron content to maximise its translucency. Support bars and trusses are as slender as possible to minimise their shadow. The ground is covered in white plastic to reflect and amplify the light. In winter high-pressure sodium lamps supplement the natural light for up to 17 hours a day, but the plants also need to 'sleep’ in order to distribute the glucose and other benefits of photosynthesis, so the lights are turned off between four and 11pm.

The pepper greenhouse is no less striking. Pleun van Malkenhorst, who runs it for another of Fresca’s partners, Rainbow UK, and is also Dutch, uses a bicycle to monitor its 20 acres. Pepper plants are not as flexible as tomato vines, so they have to be grown vertically not horizontally – 260,000 plants towering 12-13 ft upwards and festooned like Christmas trees with green, red, yellow or orange fruit. Van Malkenhorst plucks one off. He munches it like an apple as he explains how his wife works in a farm shop and continually hears customers describing Thanet Earth’s produce as chemically induced or somehow unnatural. It is a myth that peppers grown outside are tastier or healthier, he says. 'Ours are absolutely better because we can put energy into the fruits and get maximum sugar development in them. What we do here is 100 per cent focused on taste and quality.’

Liz Wright disputes that. 'I firmly believe that fruit and vegetables grown yourself taste better,’ she says. Be that as it may, it is certainly the case that Thanet Earth bears about as much relation to the traditional notion of agriculture as a Lord’s Test match does to a game of rounders in a park. Its produce is marketed as 'Grown in Kent’ but there is nothing resembling a field, and not a speck of Montgomery’s chalky Kentish soil in sight. There are no tractors, no ruddy-faced farmers in dungarees, no heaps of compost. The glasshouses are more like huge aseptic laboratories staffed by scientists and technicians.

The seasons have been all but eliminated in the sense that tomatoes are now produced all year round, cucumbers from mid-January to November, and peppers from March to November. The ripening of the crops can, to an extent, be advanced or retarded to meet periods of peak demand such as bank holidays or major sporting events. Cloudy summers reduce production levels, but there are no droughts inside these glass walls, no violent storms, frosts or sudden cold snaps. There are no abject crop failures or devastating pestilences because rock wool, unlike soil, does not contain bacteria and fungi. The biggest threat comes from viruses, hence the protective clothing, restricted access and careful sourcing of plants, which have so far prevented any disaster.

Van Straalen still imports bees by the hive-load to pollinate his tomatoes, but the plants are grown at a height that allows the fruit to be picked without bending or stretching. Driver-less lines of carts follow an induction loop as they carry the picked produce away to be packed. There are no gnarled, wizened or blighted specimens in those carts – just tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers that are almost uniformly perfect in shape, size and colour. Even the cucumbers are dead straight, grown that way by suspending them from a height and using gravity.

Thanet Earth employs a 40-strong quality control department, a necessary expense because even a few flawed fruits can jeopardise an entire delivery to a supermarket chain. It claims that only two per cent of its produce fails to meet the retailers’ exacting standards.

Most of the 600 people working at Thanet Earth appear to believe passionately in what they do, and angrily reject the charge that they are somehow perverting nature or creating something artificial. 'We’re producing high-quality food in a controlled environment, but it’s still a crop that grows and needs food, water and light. It’s just like the maize crop across the road,’ says Ian Craig, who admits he has 'no patience whatsoever’ with those who deride Thanet Earth’s produce as 'Frankenfood’.

'We use technology to control the conditions in which the crop grows, and that enhanced control gives us higher yields and better quality. But the principles we use are exactly the same as outdoor farmers’,’ van Straalen insists.

He says organic farming benefits from 'fantastic marketing’, but dismisses as 'romantic nonsense’ the idea that tomatoes grown outdoors in soil and unfiltered sunlight are somehow better or tastier than his own. 'I love my tomatoes,’ he declares. 'I actually feel like I have a relationship with the crop. Each variety has its own distinct personality.’ His favourite is the Sunstream. 'It’s very temperamental. It’s wild. It needs to be tamed.’

Thanet Earth’s management goes further, trumpeting its green credentials. It turns to chemical pesticides only as a last resort – instead it imports large quantities of 'good insects’ such as wasps and macrolophus, which prey on 'bad insects’ like whitefly, caterpillars and spider mites. The complex is largely self-sufficient in water, channelling rain from its glasshouse roofs into four large reservoirs and even collecting the condensation inside the glasshouses.

It has its own gas-fired generators for electricity, but captures the heat and carbon dioxide that they emit as waste and pumps them back into the glasshouses. Even the defective produce is turned into animal feed or compost.

Obtaining planning permission for Thanet Earth was no problem in an area suffering from chronic unemployment. Its glasshouses seem preferable to having thousand of acres of farmland covered in plastic, as happens in Spain and other Mediterranean countries. The complex is also relatively close to its customers, cutting the transport requirements that can be involved in delivering fresh produce to British shops. Once a day, by contrast, a Boeing 747 carrying beans and peas from Kenya roars overhead before landing at the nearby Manston airport.

Judy Whittaker, Thanet Earth’s communications manager, blames some of the cheap, imported produce, which is often grown too fast in countries such as Spain and Morocco and picked before it is ripe, for giving the entire glasshouse industry a bad name. 'A common complaint we hear is that tomatoes don’t taste like they used to. At 69p a pack I’m not surprised. With respect, you have to change the tomatoes you buy. You get what you pay for,’ she says. 'It’s not the soil that provides the flavour in a tomato,’ she contends. 'It’s the variety and the feed. Our tomatoes rival any we’ve come across yet.’

Thanet Earth’s critics are hard to please. Felicity Lawrence, the investigative food writer, accepts that the complex has worked on its eco footprint but argues that it is 'still locked into an industrial model of food production that is inherently unsustainable, both environmentally and socially. It is part of a carbon-intensive centralised supermarket distribution system that trucks food vast distances.’

Graham Smith, the editor of Smallholder magazine, asserts that 'all the experts, from Oxfam to Prince Charles, agree that the best model for the sort of food production needed to satisfy a growing global population rests with small-scale, locally based agricultural schemes.’ He contends that the energy, packaging and distribution requirements of 'factories’ such as Thanet Earth render it unsustainable.

But Thanet Earth is not going away. It is preparing to build three more of its glass palaces over the next few years, and that should at least help to reduce Britain’s dependence on foreign produce. At present the country imports roughly 40 per cent of the food (and 80 per cent of the tomatoes) that it eats, but global competition for that food from booming economies such as China and India is rising. 'We’re not going to feed the country by wandering whimsically around a field with a trug,’ Whittaker says.

Nor is it clear how the world will be able to feed two billion more people by 2050 unless it adopts the sort of intensive production methods practised by Thanet Earth – a challenge made all the more daunting by climate change and the growing competition for land and water.

It is time for me to leave. Whittaker expresses regret that the public cannot tour the glasshouses as I have. 'We have nothing to hide. We’re confident in what we do,’ she insists as she hands me a bag of produce to take home. My family and I sample it that evening. Some of the tomatoes are sweet and tasty, others a little bland. The peppers are firm and crunchy, and the cucumber – well, what do you expect of a vegetable that is 96 per cent water?

Such judgments are entirely subjective, of course, so I call Montgomery to ask for his opinion as a traditional farmer from Kent, the so-called Garden of England. I had expected some ambivalence at least, but he offers a surprisingly robust endorsement of Thanet Earth. He would not have sold his land had he not believed in the project, he says. 'The image of a farmer with his horse and cart is pretty much past. Technology is pushing us all forward. I think it’s a very positive development... I see absolutely no reason why what’s coming out of there is not as good, flavour-wise, as what you can get anywhere else.’