December 2013

There will be services, vigils and wreath-layings galore to mark the centenary of the outbreak of World War One in 2014. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is planting tougher grass at its French and Belgian cemeteries to cope with record numbers of visitors, and has quadrupled its production of headstones to ensure all 1.2 million graves are in pristine condition. Largely unnoticed amid all the commemorations, the clearing up of the battlefields will continue unabated.

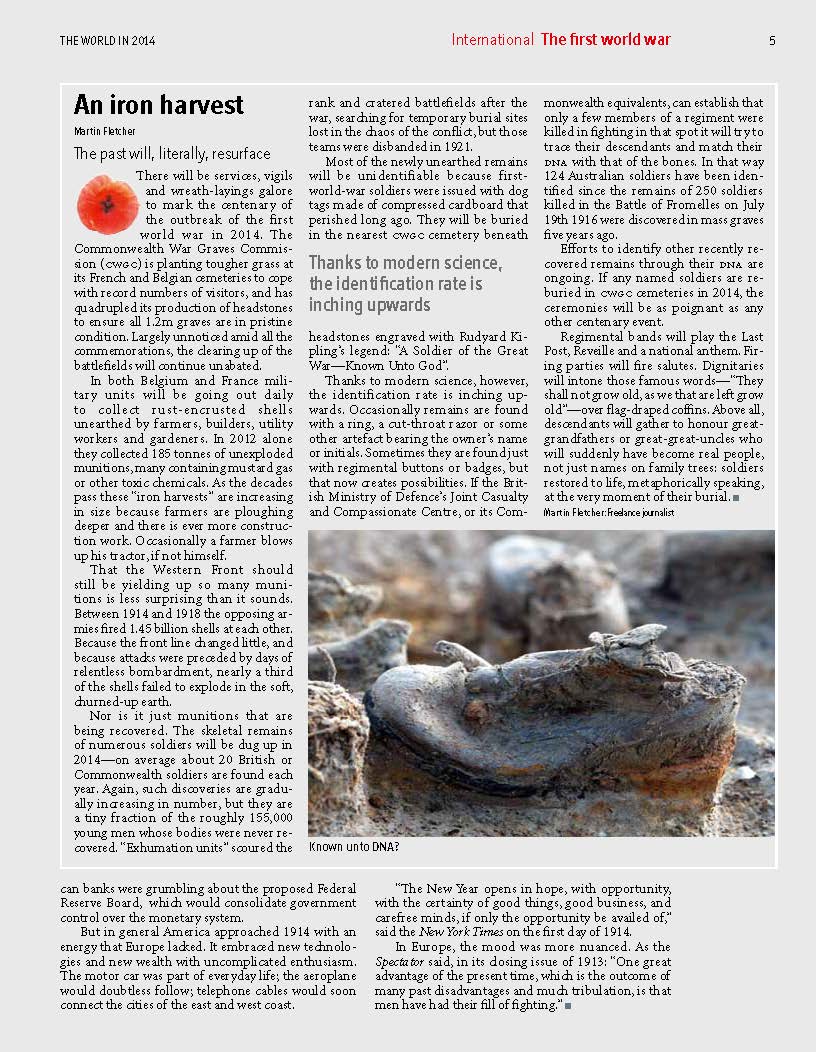

In both Belgium and France military units will be going out daily to collect rust-encrusted shells unearthed by farmers, builders, utility workers and gardeners. In 2012 alone they collected 185 tons of unexploded munitions, many containing mustard gas or other toxic chemicals. As the decades pass these 'Iron Harvests' are actually increasing in size because farmers are ploughing deeper and there is ever more construction work. Occasionally a farmer blows up his tractor, if not himself.

That the Western Front should still be yielding up so many munitions is less surprising than it sounds. Between 1914 and 1918 the opposing armies fired 1.45 billion shells at each other. Because the front line changed little, and because attacks were preceded by days of relentless bombardment, nearly a third of the shells failed to explode in the soft, churned-up earth.

Nor is it just munitions that are being recovered. The skeletal remains of several British and Commonwealth soldiers will be dug up in 2014 – on average about 20 are found each year. Again, such discoveries are gradually increasing in number, but they are a tiny fraction of the roughly 155,000 young men whose bodies were never recovered. 'Exhumation units' scoured the rank and cratered battlefields after the war, searching for temporary burial sites lost in the chaos of the conflict, but those teams were disbanded in 1921.

Most of the newly-unearthed remains will be unidentifiable because World War One soldiers were issued with dog tags made of compressed cardboard that perished long ago. They will be buried in the nearest CWCG cemetery beneath headstones engraved with Rudyard Kipling's legend: 'A Soldier of the Great War – Known Unto God'.

Thanks to modern science, however, the identification rate is inching upwards. Occasionally remains are found with a ring, a cut-throat razor or some other artefact bearing the owner's name or initials. Sometimes they are found just with regimental buttons or badges, but that now creates possibilities. If the Ministry of Defence's Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre, or its Commonwealth equivalents, can establish that only a few members of a regiment were killed in fighting in that spot it will try to trace their descendants and match their DNA with that of the bones. Thus 124 Australian soldiers have been identified since the remains of 250 soldiers killed in the Battle of Fromelles on July 19, 1916, were discovered in mass graves five years ago.

Efforts to identify other recently-recovered remains through their DNA are ongoing. It remains to be seen whether any named soldiers will be reburied in CWGC cemeteries in 2014, but if they are the ceremonies will be as poignant and moving as any other centenary event.

Regimental bands will play the Last Post, Reveille and national anthem. Firing parties will fire salutes. Dignitaries will intone those famous words - “They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old” - over flag-draped coffins. Above all, descendants will gather to honour long-forgotten great-grandfathers or great-great-uncles who who will suddenly have become real people, not just names on family trees - soldiers restored to life, metaphorically speaking, at the very moment of their burial.