A KGB Defector Speaks Out / Telegraph Magazine

Interviewing a KGB defector is complicated in an age when Valdimir Putin’s regime regularly murders its opponents, both at home and abroad. It is all the more complicated if, like Valdimir Popov, the defector is about to publish a book chronicling the infamous history of the KGB and its present-day successor, the FSB, in detail worthy of a John Le Carre novel.

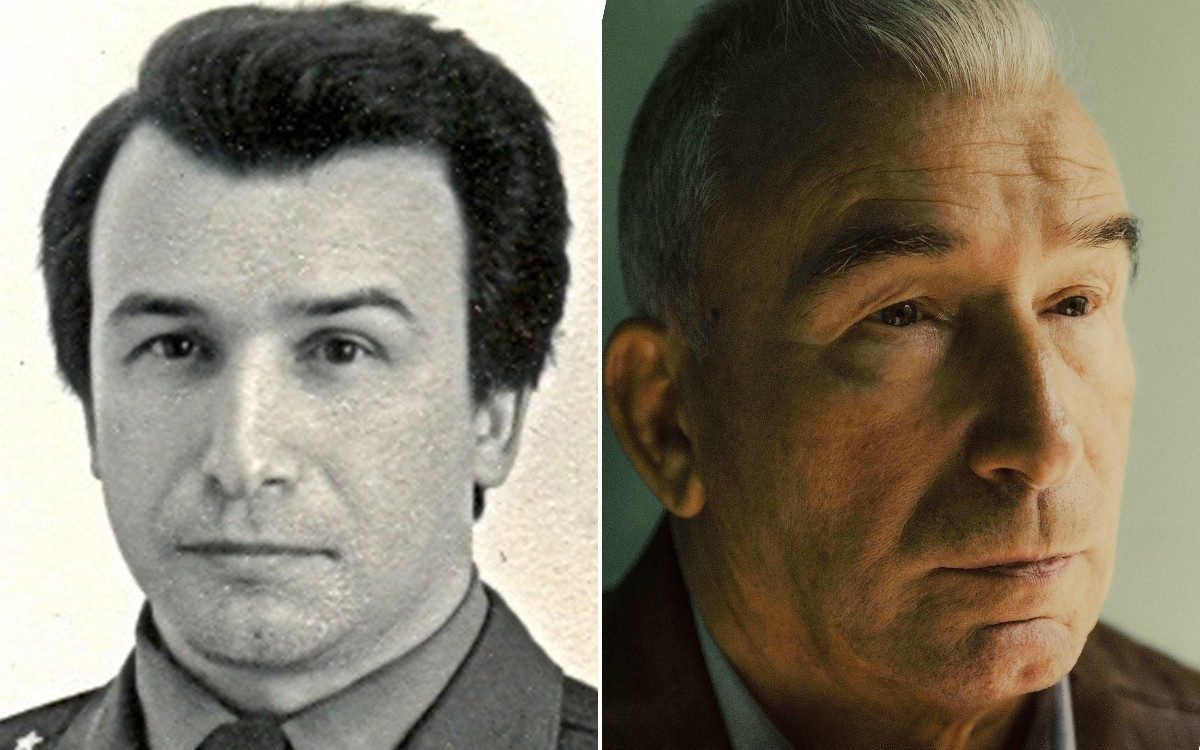

He agrees to be interviewed only on condition that I do not identify the Canadian city where he now lives. We meet in a location of his choosing - a friend’s empty office in that same city whose address I have received at short notice and that is well away from prying eyes. He will be photographed only against an unidentifiable background. He readily acknowledges that he has checked me out before we meet. Even then he brings his own bottle of water. Had I brought coffee with me, he adds, he would have refused to drink it.

Popov’s caution is entirely understandable. He remembers all too well the agonising, drawn out death of Alexander Litvinenko, another outspoken KGB defector poisoned by the radioactive polonium with which Putin’s agents laced his tea in a London hotel in 2006. “It was very deeply emotional for me,” he says in broken, heavily-accented English. “He made a big mistake in my view. He kept in touch with former colleagues (in the KGB). That made it easy to kill him. They knew where he was.”

But he also says it was Litvinenko’s appalling death that finally convinced him to start speaking out. It was his “duty” to expose how Putin and his former KGB colleagues had seized control of Russia following the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 and turned it into a rogue state bent on rebuilding its old empire.

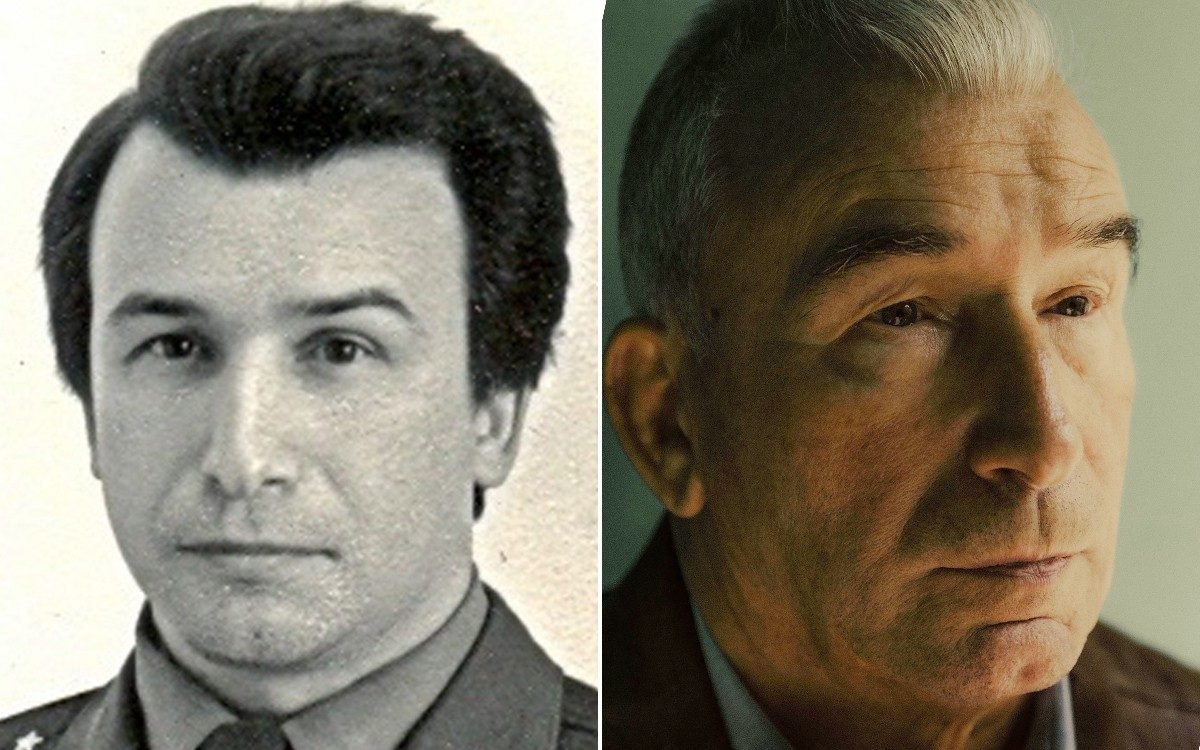

“I thought I have to do it,” says Popov, a soft-spoken, silver-haired man of 76 who wears a leather jacket and open blue shirt. “Every single day I am ready to be killed. I worry just about my family, not about me. If you’re ready you are not afraid.”

*****

Popov was born in Moscow in 1947. His father had lost a leg in the war, could not work and died young. His mother was a factory worker. He left school at 15, spent three years in the Soviet army, serving in the former East Germany, and then studied law at night school while working in a factory by day.

Towards the end of his course the KGB came to recruit him. He resisted, but was told he would be denied a diploma and have no future if he was not “loyal to the Soviet Union”.

He joined in 1972. His first job was to deliver mail within the Lubyanka, the KGB’s headquarters. After two years he tried to leave, but was promoted the KGB’s 5th Directorate and charged with assessing whether scientists, military engineers and other Soviet citizens privy to sensitive information should be permitted to travel abroad.

From there he graduated to the section of the 5th Directorate that monitored and recruited writers, artists, composers, journalists and other cultural figures. Those that did not cooperate were denied public platforms or the chance to travel outside the Soviet Union.

Three years before the Moscow Olympics of 1980 Popov was promoted again, this time to a section of the 5th Directorate created to prevent any propaganda reversals before and during those Games. He helped recruit athletes, coaches, medics and others to inform on suspect colleagues. He travelled abroad with Soviet sports teams to try and prevent defections - not always successfully.

Not a single Soviet competitor failed a drugs test during the Moscow Olympics because, he says, their urine samples were secretly swapped for those of ‘clean’ officials. Not a single western athlete failed a test either. “If only the Soviet (athletes) didn’t get caught there would obviously be something wrong so nobody was caught,” he says.

He also contends that the KGB recruited Juan Antonio Samaranch, and orchestrated the Spaniard’s election to the presidency of the International Olympic Committee in 1980, after he was caught smuggling historic artefacts out of Russia and became susceptible to blackmail.

By the late 1980s Popov had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, charged with improving the KGB’s image, which was ironic as he was desperate to leave an organisation he had secretly come to detest. His repeated requests to resign were ignored. “It’s easy to go in, but very difficult to go out,” he says.

Then, in August 1991, hardline Communists mounted a coup against the reformist president Mikhail Gorbachev. Popov says that the KGB hated Gorbachev, and that most of its officers simply disappeared instead of helping the beleaguered president. He seized his chance. “I told my supervisor I didn’t agree with what was going on and walked out.”

Popov says he is “not proud at all” of his 20 years of KGB service, but feels no shame either. “I didn’t make bad things for people when I was a KGB officer,” he insists. Though he and Putin joined the KGB within three years of each other, they never met. “I heard nothing about him, absolutely nothing, like many people,” he says, suggesting Putin was at that time a nobody.

He set up a business importing gloves, shoes and other products that vanished from shops during the Soviet Union’s subsequent collapse, but his former KGB colleagues did not forgive him for his desertion. “They called me a traitor,” he says.

He claims that on several occasions they tried to intimidate or kill him. He was attacked with a knife while parking his car. He was pushed down a subway escalator. He was shot at while driving. He went into hiding, and gunmen shot his nephew through the opaque window of his mother’s apartment believing it was him. The nephew survived but his friend was killed. “They hate me and I hate them,” he says of his former KGB colleagues.

He had a passport, and realised he had to leave Russia. The US refused him a visa, so in 1995 he went to Canada, a country that he had visited and admired while chaperoning Soviet sports teams. He confessed his past and offered to cooperate with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

For two years he lived alone, working night shifts in a bakery and as a pizza delivery man. Back in Moscow his wife was violently assaulted, and unknown assailants tried to seize his 12-year-old son while he was playing outside their apartment. Finally, in 1997, Popov was granted refugee status and his family was allowed to join him. He became a cab driver and watched from a distance as Putin, in Moscow, ruthlessly and systematically cemented his power and turned post-Soviet Russia back into a police state, eliminating his opponents one by one.

Boris Nemtsov, Alexei Navalny, Boris Berezovsky, Anna Politkovskaya, Sergei Skripal, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, Mihail Lesin, Yevgeni Prigozhin - the list of Putin enemies who have been killed, died in mysterious circumstances or narrowly survived assassination attempts goes on and on.

Livinenko was poisoned in November 2006, not long after writing a book with Yuri Felshtinsky, a Russian American historian based in Boston, Massachusetts, entitled Blowing Up Russia: The Secret Plot to Bring Back KGB Terror. The book alleged that in the late 1990s the KGB fabricated terrorist attacks in Moscow to justify launching the war in Chechnya that would win Putin the presidency in 2000.

Eight months later Popov wrote to Felshtinsky, offering to put his inside knowledge at his disposal to fight the resurgence of the KGB, by then renamed the FSB, under Putin.

“What is happening in Russia has become a constant source of alarm for me,“ he wrote. “During my years of service, I became completely disillusioned in the ideals that state security was called upon to serve—its country and its people. The longer I served, the more clearly I saw

that the KGB, one of the most important institutions of government, was once again acquiring the dark features of a repressive, rather than protective organization, that it had in the 1930s, a period of brutal repression in our country’s history.”

The first results of Popov’s collaboration with Felshtinsky were books entitled The Age of Assassins: The Rise and Rise of Vladimir Putin and The Corporation: Russia and the KGB in the Age of President Putin, both jointly written with a Russian political scientist named Vladimir Pribylovsky.

Popov’s name was omitted from both books to protect his aged mother and sister, who still lived in Moscow. It was a sensible move. Pribylovsky was later found dead in his Moscow apartment. Popov believes he was killed by Putin’s regime. “In my opinion, it looks like it,” he tells me.

Popov’s mother and sister have both since died. To my surprise, the former KGB officer dissolves into tears as he tells me how he was unable to return to Russia for their funerals, and takes a minute to compose himself before resuming the interview.

Over time Popov grew bolder. His next book with Felshtinsky was The KGB Plays Chess, and this time his name appeared on the cover although he knew it would make him a target. “My wife completely disagreed. Even today she shows some concern,” he says.

The book told, amongst other things, of the KGB’s often successful efforts to recruit Soviet chess Grand Masters, and the extraordinary lengths it took to ensure that one of them, Anatoly Karpov, beat the dissident Garry Kasparov in the final of the 1984 World Chess Championship in Moscow. Popov says the KGB bugged Kasparov’s rooms so it could hear him planning tactics with his team and relay them to Karpov. When Kasparov fought back from early defeats the contest was mysteriously abandoned.

Popov also relates how the KGB sought unsuccessfully to end an affair between Boris Spassky, another Russian Grand Master, and a French diplomat by planting pubic lice in her underwear. Their efforts failed. Spassky subsequently married the diplomat and emigrated to France. When The KGB Plays Chess was published in Russia the FSB bought every copy and destroyed them, Popov says.

The new book, From Red Terror to Terrorist State, is perhaps the culmination of Felshtinsky’s collaboration with Popov, detailing the history of the Russian intelligence service from its formation by Felix Dzerzhinsky following the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 to the present day.

Most pertinently, it explains how the KGB and FSB manipulated events following the Soviet Union’s collapse to ensure that one of its own, Putin, succeeded Boris Yeltsin as president, and how it has since consolidated its power over every part of the Russian state, crushing all moves towards democracy. Coincidentally, a week before my interview with Popov, a new statue of Dzerzhinsky was erected outside the Lubyanka to replace the one torn down in those heady days after Yeltsin faced down the attempted coup of 1991.

The book further argues that Putin, who once called the collapse of the Soviet empire “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the [20th] century, is determined to rebuild much of that empire and create a new Russkiy Mir (‘Russian world’). Its tools are military aggression - hence the Ukraine war - allied with propaganda, electoral interference and the co-opting of foreign politicians in order to weaken the West and divide Nato and the European Union.

One lengthy chapter explains how the Kremlin identified the “ambitious opportunistic money-obsessed playboy Donald Trump” as fertile “working material” back in the 1990s. It proceeded to rescue him from impending bankruptcy in the late 2000s, pour money into his business ventures and fight to secure his victory in the US presidential election of 2016. “The Kremlin would harvest ample fruit of its labour (sic) and reconstruct the world during Trump’s four years in office,” it states.

The book strongly implies, but does not explicitly state, that the KGB recruited Trump as an agent. I asked Popov if that happened. “It’s possible, yes,” he replies.

****

Popov agrees that the war in Ukraine is going badly for Putin, but he is not optimistic about the future.

He dismisses the possibility of the Russian people rising up against Putin because, he says, the Kremlin’s propaganda machine and instruments of repression are too strong.

He believes there is a chance that the FSB could itself oust Putin, and then blame him for the misconduct of the war, but fears he would simply be replaced by someone equally bad or worse. He names Nikolai Patrushev, a former FSB chief and the hardline head of Russia’s Security Council, as a possible successor.

He further believes that even now the West fundamentally misunderstands the nature of Russia’s present leadership and its determination to continue prosecuting the war regardless of the cost. It could use nuclear weapons as a last resort because “these are crazy people”, he says. It would never accept defeat because “the Russian mentality it’s ‘empire, empire’. (It must be) a big country, a strong country. Everyone in other countries must be afraid of Russia…it’s deeply in their mentality. Russia will be always the same, always”.

In the meantime Popov will continue to live in what he calls “limbo” in Canada. Unlike his wife, he has no desire to return home, and knows he would be imprisoned or killed if he did. “I completely hate Russia now,” he says. He still has nightmares about finding himself back there, and will not speak Russian at home.

He says he is happy in Canada. He works in a small business whose name and nature he cannot disclose for security reasons. His son, now 41, has married a French Canadian and works as a supervisor in the construction industry. He has two young granddaughters, and proudly shows me a picture of one of them on his mobile telephone.

But he leads a fearful, circumscribed existence. His wife and son acquired Canadian passports in 2005, but his own application for citizenship has been denied because of his KGB past. He cannot leave the country. He has to apply for a new work permit every six months. He says the only official document he owns is his driving licence.

Moreover the price of his courage, or what he calls his “mission”, is eternal vigilance. Before entering the lift in his apartment block he makes sure that is not being followed. He routinely checks his car for explosives. He does not talk to other exiled Russian dissidents for fear of being traced. He refuses to talk to Russian journalists, even on-line, for the same reason.

Our interview over, Popov poses for photographs, shakes hands, then walks away down a mundane street in a peaceful city in a western democracy several thousand miles from Moscow. It seems inconceivable that he could be targeted here, but he knows full well that he is about to provoke Putin once again. He also knows that the reach of his former KGB colleagues is very, very long. “Of course it’s dangerous,” he says.